Many people attempt to undermine the material reality of sex by highlighting weird and wonderful examples of variation in the natural world.

“But clownfish change sex [therefore sex is not objectively defined]”

“But some animals don’t have X/Y chromosomes [therefore the human system is unreliable]”

“But some people have reproductive disorders [therefore sex doesn’t exist]”

Here is my response.

Clownfish. These fish, like many others, are sequential hermaphrodites. In the case of clownfish, a group contains one dominant female and if she is removed from the group, a male changes into a female to replace her. Sex change in clownfish occurs when the testicular tissue of the bipotential gonad is regressed and ovarian tissue promoted.

How to recognise a female clownfish: She’s usually big. Oh, and she makes large gametes.

Anglerfish. These fish display extreme dimorphism between the sexes. The tiny males permanently fuse themselves to a female, adopting a parasitic lifestyle for the privilege of being first to contribute sperm to laid eggs.

How to recognise a female anglerfish: She is big and can be decorated with several parasitic males. Oh, and she makes large gametes.

Birds. Birds genetically determine sex, but using ZW, not XY, chromosomes. Males, with ZZ, are the homogametic sex and females, with ZW, determine the sex of babies. It’s not clear how ZZ triggers male development.

Crocodiles. Sex is determined by environmental temperature during the middle third of development. Male development requires intermediate temperatures, while females develop at lower or higher extremes.

Platypuses. Platypuses have five pairs of sex chromosomes. Females have five pairs of XX and males five pairs of XY, but pairs 3 and 5 look a bit more like ZW chromosomes (see birds above) than mammalian XY chromosomes. And the way they segregate these chromosomes when they make gametes is just wild. I guess you could say they’re complicated creatures.

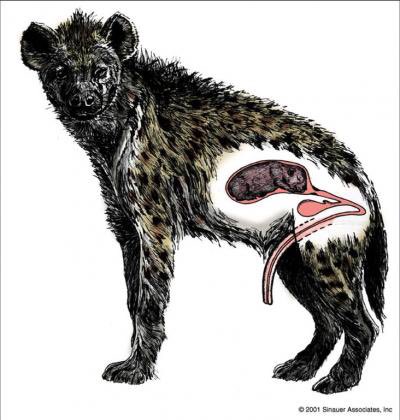

Hyena. Female spotted hyenas have a pseudo-penis which is internalised during mating and through which she gives birth. Because retraction of this pseudo-penis is controlled by the female, she is the sole arbiter of when intercourse will occur, suggesting that female spotted hyenas cannot be raped.

How to recognise the female: She’s giving birth through a massively overgrown clitoris, what more do you want as an identifying feature? Oh, and she makes large gametes.

Flatworms. More simultaneous hermaphrodites. When it comes to reproducing, individuals penis fence to determine which will take the male role. Most of the time, no-one wins and they each, perhaps dejectedly, spaff over the other.

Bees. Sex in bees is determined by number of chromosome sets. Females have two pairs of 16 chromosomes (32 total) while males have a single set of 16 chromosomes. Males develop from unfertilised eggs and their only genetic material is derived from their mother. Male sperm is used to create eggs with two pairs of 16 chromosomes. This means male bees have neither a father nor sons. But he must have a grandfather and may have grandsons.

Asparagus. No sense of sexed self and no plausible mechanism for social construction of gender. How to recognise the female: she makes large gametes.

Tuatara. Sex determination so extremely temperature sensitive that climate change is causing them to be largely male. How to recognise the male: he makes small gametes. He can also be seen looking annoyed at enforced incel status.

Peafowl. Sexual selection gone mental. How to recognise the female: she makes large gametes. And she’s not a massive freaking showoff, like this fella…

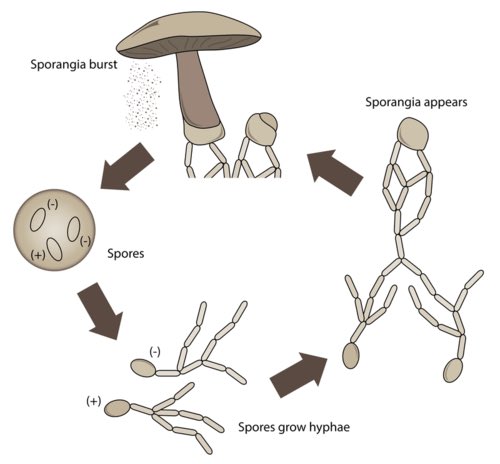

Mushrooms. Delicious. How to recognise the female: there are no females (‘there is only Zuul’). ‘Female’ and ‘male’ are predicated on two and only two differential gametes, and fungi don’t have them thingies, settling instead for equivalent gametes labelled +/-, or A/B, or yawn.

Head lice. Annoying buggers. The female transmits chromosomes she inherited from either her mum or dad; the male *only* transmits chromosomes he inherited from his mum. How to recognise the female: she makes large gametes.